Stories

Our Heritage Garden

If gardens reflect those who cultivate them, then a school garden can be a cacophonous affair.

This is true of the Heritage Garden at Madison Middle School. Our herb garden spills over with creeping thyme, overgrown tomatoes and bunches of chives. A bright red coop contains a flock of noisy chickens whose clucks and coos fill the airwaves. A plastic hoop house captures the blazing heat and nourishes the plants inside. We see beds of greens, bursts of marigolds and rows of messy perennials all around. A rickety old barn sits in the background next to a forest filled with lichen-covered trees. In the middle of this lively scene lay several compost bins, which drew the attention of a 7th grader named Brianna one Spring afternoon.

“Institutional needs often trump environmental ones,” we responded. “There are barriers in place that make it hard for schools to make large-scale changes,” we admitted. Brianna was not satisfied with these adult responses, mired in the stagnant muck of status quo. In fact, they spurred her disapproval. “What happens to all this food growing here?” she countered. “I know we use some of the herbs in PAGE, but why can’t we eat this food in our lunches? I don’t like what they serve us. It has no flavor! They’re not even allowed to use salt to make it taste good!”

The other girls chimed in, offering their own stories of dissatisfying school lunches.

“Yes, this is a problem,” we agreed. “What should we do about it?”

Of course, the PAGE girls did not solve the problem of nutrient-lacking and flavor-depleted school lunches that afternoon. But Brianna started a conversation based on a close observation and a notion that things could be better. She questioned her adult mentors and pushed back against our conventional responses. She inspired her peers to discuss a complicated issue and begin to think of creative solutions. A budding leader, Brianna represents the change that is possible when Appalachian youth are empowered to imagine and create the world they want to inhabit.

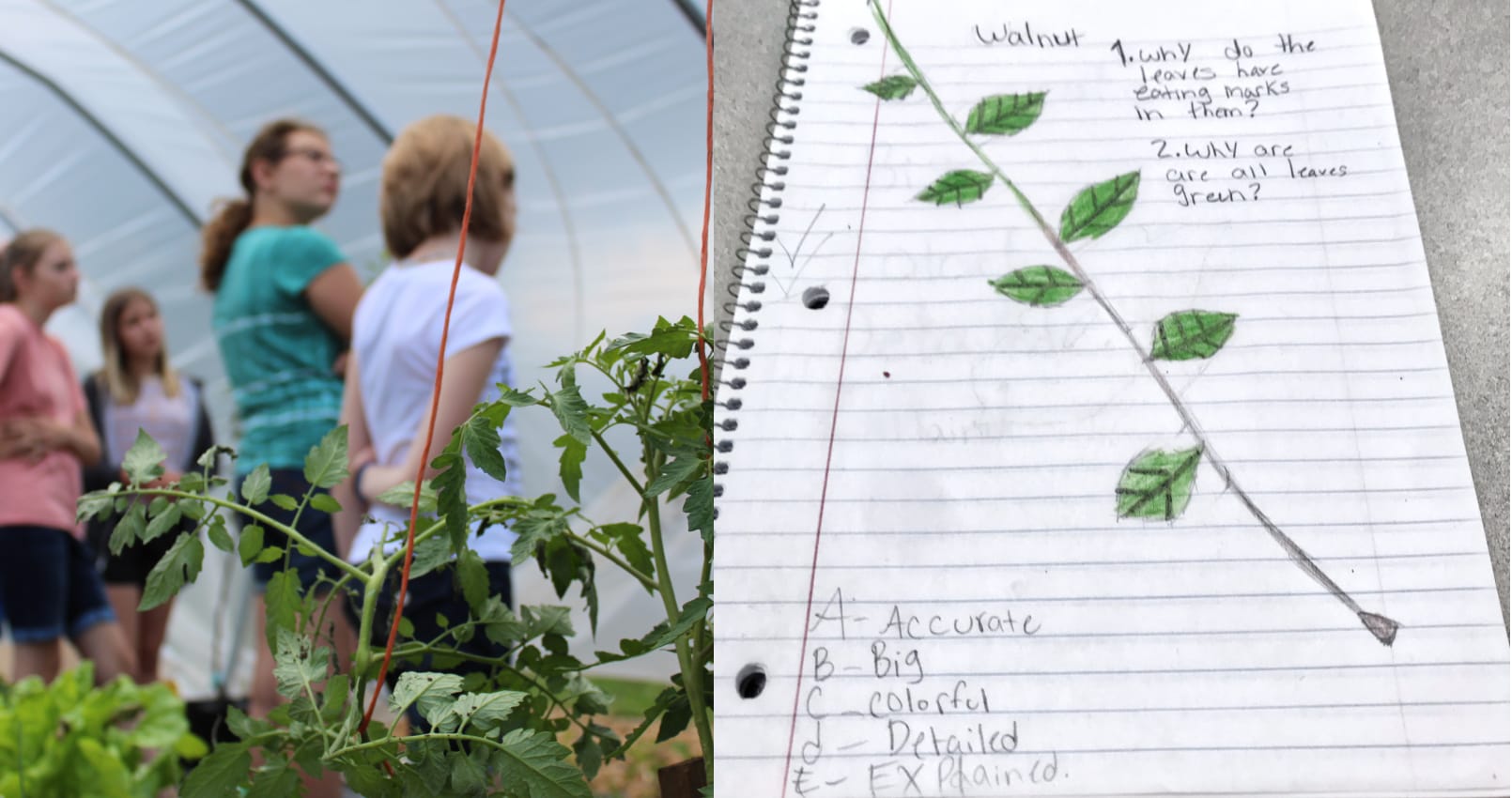

With so much to explore in the garden, it can be easy to get swept up in the selection. Having engaged facilitators to guide our students through these interconnected worlds offers a chance for them to tune in. On a warm and cloudless October day, during an exploratory lichen walk with local Mars Hill Professor Laura Boggess, one 8th grader named Sophia was enchanted by this newfound knowledge of a secret world right at her fingertips. Her eyes danced with intrigue as she patiently waited to ask the question brewing inside. Kneeling beside a fallen branch, she began to meticulously sketch a piece of usnea in her garden journal, pausing every so often to investigate the specimen. Her garden journal is filled with many such observations of this space, from stoic conifers situated in the shade on a sloping hillside to pressed marigolds and goldenrod surrounded by notes on their classification and placements in the garden.

STEM can feel daunting to students. Cultivating a living lab where lessons come to life is key to our objectives. By moving through the seasons with our garden, students are able to organically align their minds with the rhythms of an ecosystem. Simple tasks like mulching the garden beds with recycled materials signals interiority and the impending winter, just as seed saving harnesses hope for the next season. Low stakes, high engagement activities in the garden create room for students to wonder aloud and to feel empowered in their inquisitions. At its core, science is asking good questions, and by surrounding our students with fruitful opportunities to explore, and knowledgeable adults to guide them, the stressors of in-class learning can take a backseat. Walking through the forest that day, Sophia looked at the lichen as a scientist does! She observed closely, asked simple questions, and reflected on her observations in her lab journal. Imagine what other questions Sophia might ask (what other worlds will she discover??) as she continues down her own curious/future pathways…

The heritage garden offers space for personal interest to blossom without fear of judgment or a sense of hurry. In the late spring, a 7th grader named Scarlett joined PAGE, often quietly observing from the side or chatting with a friend. During our journaling time, Scarlett headed into the greenhouse to look around. She stumbled across a vibrantly colored orb weaver hanging against the warm plastic. Energized by her discovery, but unsure how others would feel, she approached Ryn, a staff member, and told them of her new greenhouse friend. With encouragement, Ryn followed Scarlett to observe the spider, noticing the smile that spread across Scarlett’s face as she excitedly led the way. Over time, Scarlett’s outward engagement grew, feeling empowered to ask questions and share in the hands-on lessons. Returning in 8th grade, Scarlett now carried a quiet assuredness in herself, walking the gardens alone and jotting down notes and reflections of her findings. Once again, she found a spider's nest, newly hatching just before her eyes. Once again, she called over Ryn, overjoyed by her garden discovery of a new specimen. Scarlett bent down with camera in hand, capturing a few photos of the nest.

In the heritage garden, we watch students develop a sense of pride and ownership in a space that they share not only with other people, but with myriad other interesting life forms.

So-called pests, like spiders or wasps, might elicit trepidatious wonder in some and wholehearted desire of discovery in others. By opening the container of this semi-cultivated space to our students, they are able to approach new concepts and species with unfiltered curiosity and rapt attention.